I usually don’t eat sadza at 9am but for once I was truly looking forward to a hot plate of the staple at such an early hour. I had been invited by William Gwata, inventor of the Gwatamatic to visit a site with one of his Gwatamatic installations. Yes like some I had heard of the Gwatamatic and heck I even wrote something about it but as the saying goes the proof of the pudding is in the eating. So there I was with goose bumps, not from the chilly wintry air but rather from the excitement of finally getting a chance to banish?

My first impression of seeing a live Gwatamatic in action was awe inspiring. With the sound of the boiler in the background the machine hummed and thumped, a mechanical prelude of a time when the art of cooking sadza by hand will be told in wistful tales of the ‘good old days’.

Before I had set my eyes on this mechanical marvel, Gwata, a trained biochemist told me about the conceptual history of his invention.

Studying chemistry at the Univeristy of Surrey in theUKhe realised a fundamental principle that would serve his design well. In chemistry as in most physical sciences, an experiment or hypothesis has to be reproducible, a fact that not only helps to validate the experiment but also helps to pass exams. As an intern working at theFrimleyParkHospitallaboratory he soon stumbled upon another eureka moment. As part of his duties he conducted a multitude of tests, but unlike in the varsity labs here he was presented with the much more orderly world of automated tests. As Gwata puts it ‘if you give a group of 20 students a test say to manually measure the amount of cholesterol in a sample of blood from the same source, you will get 20 different results which tend to cluster around a certain mean. With the machines however you got exactly the same result each time.”

That epiphany made him realise that the key to such reproducibility was electronic discipline, a set of parameters in electronic form, an algorithm that captured the process. His mind wandered to the cooking of Sadza, a laborious exercise. Cooking, Gwata quickly realised was really a form of chemistry. So if you could automate blood tests you certainly could automate cooking sadza. Once you had determined the electronic parameters then the variability that is associated with human cooks would be eliminated. In other words excellent sadza would become reproducible, with the same consistency every time you cooked it. Something even the most talented human cook subjected to the fluctuations of human emotions would struggle to match.

So Gwata set upon a journey to perfect this electrical code, a 12 year journey that began in earnest in 1985. So it was finally in 1997 that the Gwatamatic emerged from beta versions into version 1.0 ready for commercial use. During this time he was working for National Foods Limited sharpening his understanding of business and tinkering with the embryonic Gwatamatic. Along the way he read an Harvard Business Review article (registration required to read full article) that changed his life and steeled his nerves to take the plunge into Gwata pot of the unknown. The article spoke of the Virtual Company citing IBM’s PC business as an example. You would not find a single IBM factory anywhere in. IBM would produce their PC designs and farm them out to manufacturing subcontractors across the globe. Components from the subcontractors would then be assembled into the beige or black box with an IBM logo on it.

That realisation freed him. He realised he was in the business not of selling a product but an idea. His company name Algorhythm Pvt Ltd captures this essence. Gwata went on to emulate the IBM model and at that point he knew, with the minimal resources that he had, his dream had a fair shot at success.

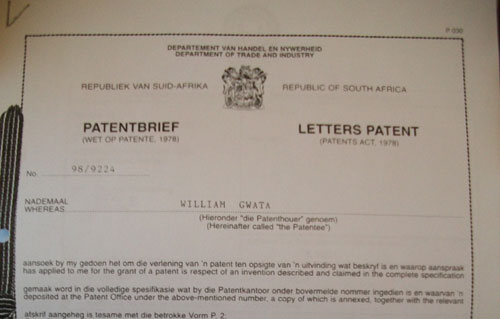

A copy of the Gwata’s Patent

So armed with $53,000 (Zimdollars) as his pension contributions refund from National Foods Staff Pension Scheme he set out to make a dent in the universe.

In the early days Gwata exhibited at the Harare Agricultural Show for two consecutive years but he soon realised that although the housewives and school children fawned over his invention they were simply not decision drivers likely to influence his sales. Since then he has not exhibited there and focused on the selling directly with the corporate bodies that form the bulk of his customer base.

When talking to Gwata what strikes you the most is his single minded clarity and analytical mint that is tinged with an impish sense of humour. You can clearly see that this is a man who has an almost intuitive feel for his work. There is a cold calculating side to his intellect however that can come across as being overly analytical. He wasn’t about to explain to me the mechanics of his invention until he was sure that I had a grasp of the appropriate concepts of physics! Not that I minded though.

So we spent time monitoring the full cycle of the Gwatamatic cooking a pot of sadza. Mind you that’s a 500lt pot that easily absorbs 95Kg of maize meal. From a practical perspective what is impressive is the fact that the machine is fully automated and there is minimal intervention by the human staff in operating it or cooking the sadza. It seems like some automata from the movie The Matrix with a mind and will of its own. The kitchen staff are totally freed from this particular task. (Please note the full technical run down of the machine will be given in Part II of this feature.)

The practicality of Gwata’s invention is not lost on Taurai Chinyamakobvu an IT consultant and analyst based inJapanwho says “One very important thing they teach in technology schools (especially the Japanese schools emphasise it) is that an invention is different from an innovation. The major difference being that an invention not accepted by society is not an innovation and successful commercialization of an invention is key. Successful commercialisation requires a clear business model, a strong sense of marketing and venture capital.”

Chinyamakobvu is dismayed by the lack of technical innovation inZimbabwe“(what has) boggled my mind is why our people do not invent anything, and why our engineers cannot even make a bicycle. There is so much technology around me in Japan, and I see lots of common sense inventions and innovations.” It is these common sense inventions that are lacking inZimbabweargues Chinyamakobvu, of which the Gwatamatic address one such issue.

Gwata is a firm believer that there needs to be a greater presence of technical and scientific skills in the top management and government leadership. He notes the dire state of most major Zimbabwean companies which have suffered due to a lack of technical leadership. He notes that technology has changed so much and so fast that the accountants and administrators who tend to dominate Zimbabwean industry have been left behind. “When you look at the leadership inSilicon Valleythe founders and leaders of those companies have a strong technical background,” Gwata pointed out.

Gwata points out that there needs to be a significant mindset shift in Zimbabwean entrepreneurs. He argues that we have always used the lack of capital as an excuse but today having capital may actually be a hindrance because you don’t even need that much money to make your idea work. He points out thatSilicon Valleyhas harnessed the power of human capital much better than many other places. A point he stresses as we stand in the facility of one of his engineering contractors. The company produces various steel products such as oil tanks. ‘When you see oil tankers you think they need a lot of sophisticated machinery, but all you need (to manufacture them) is a crane, a cutting machine and welding machine. The real value is in the human capital, the skilled people in the plant.” It is Gwata’s position that if we as Zimbabweans and entrepreneurs realise the power and value of ideas then we could emulateSilicon Valleyand the Asian tigers. He adds that the recent economic decline inZimbabwethat has seen major companies struggle and downsize has helped our community to appreciate the value of pursuing the entrepreneurial path. When he left his job to pursue the Gwatamatic he was vilified to no end.

After witnessing the machine doing its work it was now time to validate just how good the sadza was. Well you’ve watched all those cooking shows on TV when the presenter approvingly hmmmm and aaaaahhh as they sample what’s been cooked. That’s exactly what happened. I’m yet to taste a better, smoother plate of sadza!

Please read our follow-up article: “Part II: Gwatamatic – the technical marvel” which looks in more detail at the technical aspects of the Gwatamatic as well as the business model that William Gwata has adopted.

7 comments

Chinobika mugaiwa here chimushina icho? Plus change the name Gwatamatic is a mouthful. But brilliant idea overall!

Actually yes it does..will explain it in part II of the article

clever pun!

ofcourse its a mouthful!

it makes sadza!

Names fine. its an established brand, and everyone knows it in Zim

Where is the picture

Make it Sadzamatic (automatic sadza) kikikikikiki. Useful machine, if it come in small size, i would go for one. A family size Sadzamatic or a bachelor’s sadzamatic will sell well.

[…] To read Part I: William Gwata, an entrepreneurs journey […]