I have always found the debate around net neutrality to be outrageous. What is there to debate — Should capitalism be allowed to reap the nursery sown and grown by socialism? Should corporate Darwinian free market chaos be allowed to overrun the fair, just order of the virtual realm as well? Should the world’s greatest and most successful altruistic project – an expression of a hippie socialist worldview be caged by plutocratic authority?

Nonetheless, I have always felt that millions of children in Sub-Saharan Africa, Yemen, Syria, Afghanistan, along with indigenous children from isolated and distant communities and those below the poverty line deserve to have a means at their disposal to be connected to the progress of mainstream civilisation, which often comes at their expense.

COVID-19 was supposed to be the “Great Leveller”. Instead, although the initial outbreak itself was quite indiscriminate, almost egalitarian, the disproportionate human response to it, influenced by existing social biases, contours, and inequalities, made sure that as a general crisis, it only accentuated the existent disparities in our societies. The underprivileged and socioeconomically backward have assumed varying and often overlapping roles – scapegoats, guinea-pigs, red herrings, and whatnot. The marginalised have suffered frequent dehumanisation in almost all parts of the world. Besides having limited access to survivalistic resources, both medical and otherwise, owing to disproportionate and liberal allotments of the same to the elite, the poor and the marginalised have experienced a general semblance of mistrust and blame, with every action they take, even those directed at sustaining and salvaging themselves, being heavily scrutinised and perceived as ‘stepping out of the line’. The ensurance of social justice and parity has been demoted to a second priority and quantitative, extrinsic aspects and parameters have taken great precedence over qualitative ones.

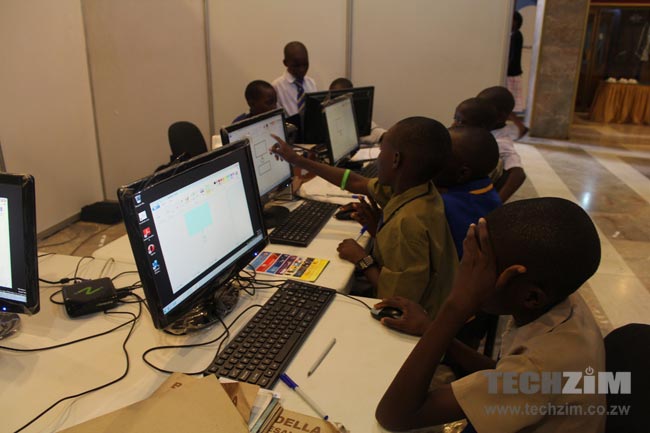

The Education Sector is no different. The virtualisation of education has, in many cases, made it less available, affordable, and accessible. The socio-economically backward in developing countries are the worst hit. Besides technological literacy and geographical convenience of connectivity, digital infrastructural costs and internet charges are major deterrents to the universal actuation of this physical-to-digital shift. There are currently no means to compensate for the lag that those who can’t access digital education will incur in the coming months and perhaps years, while realising the rapid development of physical infrastructure needed to sustain growing connectivity needs during a pandemic is extremely difficult.

A single Gigabyte of data, on an average, costs about $75 in Zimbabwe (these stats are from 2019 for 2020 figures click the link here), where about 70% of the population lived below the poverty line, and the GDP per capita was a mere $1464. The differences are even more stark if we start taking into account the real GDP and median incomes. In Chad and Malawi, the average price of a GB of data was roughly a twentieth and a tenth of the net national income per capita respectively. But unlike Central-West African nations, Zimbabwe’s problem is not the lack of interest, ability, or human resource for development. It is a paradox. Zimbabwe is a third-world nation with first-world prices and second-world dreams. Zimbabwe has one of the most literate populations in Southern Africa and has the potential to become an IT and Tech Hub. However, the COVID-19 has not only brought in disruption but also likely apprehension in future international engagement. It is thus the need of the hour that Zimbabwe strives to become self-sufficient in the technical know-how for the same. India is a good example, where rapid growths of technical institutions, IT-based service and solutions startup culture, computer literacy drives, and online accessibility were concerted and all fuelled each other in-turn. India has one of the world’s lowest internet rates, special rates for rural areas, government-initiated digital literacy and equipment drives for traditionally backward areas, and free online training facilities. Such measures have ensured that Indian digital development continues to be increasingly proactive, often working on structuring the very growth of the IT sector alongside developed nations.

For over five years, Zimbabwe has been a prime hotbed for Facebook’s equal parts controversial and ambitious ‘Free Basics’ plan (Facebook free basics is no longer on offer in Zimbabwe), a proposal that was met with prompt and harsh backlash in India, and ultimately banned. However, although Zimbabwe has the potential to become a regional IT Hub akin to India, it does not have a stable, government-supported free-market framework akin to the latter yet. That’s where the distinction comes in. For India, Free Basics could be suspected as a way to further monopolisation and the interests of a singular foreign-based giant MNC, a step that would undermine its booming free market and digital open space where government intervention has been little. Any selective waiver would thus be a step towards exceptionalistic negative regulation. Zimbabwe, on the other hand, can use free data as a means to refine its human resource, familiarise its demography with technology, equip its population with truly international accessibility to information, and build a basic, minimum digital literacy. This should be seen as a temporary suspension of net neutrality, a hiatus or phase, rather than a permanent lifting or termination. Neutrality is essential but only after a level of stable market liberalisation has been achieved. For now, any free basics strategy is a free resource, an incentive, a sort of ignitor or starter-pack for inculcating a tech-savvy learning-business complex. It’s not an irreversible transition, and once the engine is set going, net neutrality ought to be promptly reverted to.

Even after five years, the adoption of Free Basics hasn’t been smooth or pervasive. Moreover, Facebook being the owner of two of the world’s largest social media platforms undeniably possesses the potential to be an ideological or even a political force, as proved time and again by controversies in some of the world’s largest democracies. It exercises great influence over users and policymakers alike and has an immense capacity to sway and mobilise mass public opinion. It can over time also become a source of subtle, insidious, propaganda-pedalling and ideological conditioning, and also of radicalisation en masse, especially when deployed as an educational tool for the youth who could be exposed to a number of consistent biases inadvertently or systematically encountered in the information stream. It is thus not unjustified for the country’s government, administration, and policymakers to feel apprehensive about the company’s true interests, latent co-intents, and potential ulterior motives. That brings me to the crux of my proposition – Government mediation.

Ration such as foodgrain, salt, sugar, and milk, household fuel such as LPG and Kerosene, Public Transport, and Electricity are often subsidised or made available to those under the poverty line at nominal costs via Public distribution systems. However, the same government intervention is seldom seen with internet prices and telecommunication charges. Spare certain instances, such as differential rural-urban telecom pricing in India, the rich and the poor have to pay the same to use a certain quantum of telecom services, especially when it comes to internet consumption. It seems unfair to charge a child in a distant village in the wilderness for watching an hour-long educational or course-tutorial video the same as charging a well-off user in a bustling metropolitan centre for watching an hour of cinema, yet government regulatory bodies vehemently shrug off any suggestions to formulate, prescribe, and implement a content-based differential pricing scheme. Even social justice crusaders are highly skeptical of any such content-discriminate enforcement.

The reason why Net Neutrality has become such a sacrosanct and touchy subject is because its proposed alternative or counter is almost always corporate in nature. Seldom do we talk about the potential of governments regulating internet charges in this context, although we ought to be wary about this as well. Government regulation could pave the way for lobbyism, crony capitalism, and even perhaps a dystopian corporate-administrative complex. But if there’s any entity that can ensure freedom and equity in education, it is the government authorities and alienating the government from active initiative-taking and reforms in the education sector shall only serve to strengthen corporate monopolies. An extensive government-hosted, universally-accessible digital resource that contains standardised or at least authenticated educational material, and is heavily-subsidised or charge-free (the government bearing the data expenses or otherwise) would prove to be immensely helpful in reducing the accessibility and privilege rift in digital education.

The key is to strictly shield any selective internet amenity provision measures from any corporate influence. At most, reputed, reliable private entities and organisations such as eminent academic publishing houses, media houses, and open courseware platforms can be permitted to contribute purely academic and pedagogical content to the subsidised portal or pool of educational material, without citing their brand-names as the source. Any subsidy or exemption should exclusively be provided to content hosted on a centralised government resource portal and not to the same content hosted on third-party sites, even if they happen to be the original source of the content. There is still a scarce likelihood of biases, preferences, disproportionalities, and inadvertent or subtle ideological influence creeping in with such allowances, but having a unilateral content-selection, that is only the government authorities being entitled to decide the content let in, that too under unchangeable norms and criteria of intermediate source-anonymisation and categorisation will eliminate most of the scope for corporate or ulterior ideological influence upon the content. Having a unilaterality in prospective benefit from the information flow in conjugation with appropriate layers of discretionary filters will make sure that any content is hosted purely out of philanthropic intent and motive. Such a violation of net neutrality will, a tad surprisingly, be ethically and pragmatically in line with the primary intent of those who oppose any changes to net neutrality — curbing corporate influence, regulating private entities, compelling enterprises to work for societal betterment than their own, and ensuring equality of opportunity.

By Pitamber Kaushik

The author is a writer, researcher, and columnist, having previously written in Asia Times, International Policy Digest, Cultural Weekly, The New Delhi Times, The Telegraph, The Hindu, Cape Times, and the Brussels TImes, amongst others.

One response

Armed with big words, a person writes one of the most disjointed articles I’ve ever read.